The Guru of the Razor’s Edge

by

Raj Ayyar

The search for a point of origin in Indian philosophy invariably leads to a dead end. Who was the first Indian philosopher? The question does not yield a nice, cosy answer. Western philosophy has a neat little point of origin in the tinkering and stumblings of those pre-Socratic savants, who were groping to define the world in terms of a single element. Western philosophy even boasts of a founding father in Thales, who sagely concluded that the world is made of water. However, when it comes to Indian philosophy, excavating its origin is far from easy.

History is inextricably interwoven with the mythopoetic in Indian tradition. Nor is this a shameful matter demanding that we compete with the historicity of Western traditions by looking for Yajnavalkya’s bones in the Rajasthan desert. What literalists in Hinduism and other faiths share with scientistic positivists is an obsession with literal verification. Literalists and positivists alike fail to recognize that the mythopoetic imagination is not inferior to a Gradgrindish world of ‘facts, facts, facts’. By privileging the latter, we easily substitute literalism for presence. The mythopoetic opens the doors of imagination, awakens us to a sense of wonder at the sheer miracle of being and allows us to play with archetypes without shackling them within the bounds of the verifiable. The metaphors in myth point to the presence and play of the sacred which can then be experienced through meditation, prayer and other methods.

Out of the rich mix of parable, dialogue, philosophy and metaphor in the Upanishads, one figure stands out mythopoetically as one of the great early philosophers and sages of ancient India. This is the personified form of death in Hinduism. Given the myth/history mix surrounding the origin in Indian thought, surely it is admissible to view Yama in the Katha Upanishad as one of the first philosopher-teachers of ancient India.

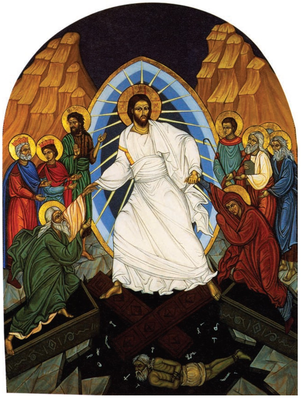

The figure of Yama is conspicuously different from many Western allegorical death personifications—for example, he is not the terrifying Grim Reaper. From the medieval morality play ‘Everyman’ to the intense, stark black & white metaphysics of Ingmar Bergman’s haunting ‘Seventh Seal’, Death is often personified in the West as the implacable adversary of life and of humankind. “You know you’re going to lose. Check!” Death tells Bergman’s knight, played by Max Von Sydow. They play a game of chess in a forbidding medieval castle, while the plague ravages the outside world as the Black Death. By contrast, Yama in the Katha Upanishad is a benign counselor, mentor and fire-testing teacher who is quite willing to initiate young Nachiketa into the mysteries of what lies beyond Death, once the young man has proved that he wants to go for broke and is not willing to settle for longevity, the companionship of apsaras and all the trappings of abundance.

What gives the Katha Upanishad its uniqueness is the portrayal of Death as a teacher rather than as the Enemy who snuffs you out. And yet, if Yama becomes the mentor and the benign guru of the razor’s edge between life and death, endless rebirths and immortality, it is entirely because of Nachiketa. It is the courage and integrity of Nachiketa that bring out the unlikely teacher in the Hindu god of death. Also, the Katha Upanishad never deteriorates into Yama’s boring dramatic monologue. This is due, in large part, to Nachiketa’s great independence and capacity for nay-saying. He is a thinking adolescent who refuses to cower, tremble or simply pay obeisance to death with superstitious fervor. He is a pleasant counter-example to centuries of Indian gerontocracy where children are meant to be docile and submissive to the supposed ‘wisdom’ of their elders.

Nachiketa is noticeably braver than Arjuna and the ‘Katha’ is considerably more dialogic than the Gita. As Professor P. Lal once remarked, the dialogue in the Gita stops with the Visvarupa. When Krishna reveals his cosmic form replete with mountains, rivers, planets, gods and asuras, poor Arjuna stares, mouth agape and knees knocking. Then he turns obsequious, apologizing for ever presuming to frame Krishna as friend and companion. One could even frame the Gita as essentially Krishna’s dramatic monologue, punctuated by occasional interjections and questions from Arjuna, barring the initial ‘Krishna, I will not fight!’ outburst. Once Krishna starts counselling the dejected Arjuna, the dialogue is over. The rest of the Gita is quite simply Krishna’s deft interweaving of Vedanta, Sankhya and Bhakti motifs into a marvelous multi-layered synthesis.

How does young Nachiketa find himself dialoguing with the great Yama-Dharma, the lord of Death? The prelude describes an interesting sequence of events leading to Nachiketa’s visit to the halls of Death. With the blunt integrity which is the privilege of some youth, Nachiketa sees through his father Vajashravasa’s political gesture to gain religious merit. Vajashravasa gives away cows that are doddering and “too old to give milk”, as gifts to the temple. He taunts Vajashravasa by asking him whether he too would be part of this ‘noble’ sacrifice. Nachiketa keeps bugging him till Vajashravasa snaps, “I’ll give you to Death!” As Eknath Easwaran points out, this may well be the ancient equivalent of an irritated parent today saying ‘drop dead!’ or ‘go to hell!’

Nachiketa thinks: “I go, the first of many who will die, in the midst of many who are dying”, on a mission to king Death.

Now, the text is beautifully non-committal about whether Nachiketa literally drops dead thanks to his father’s curse or whether his body remains in a state of suspended animation during his “mission” to King Death. If one were to hack away at the text literally, it makes no sense. We are told that Nachiketa is kept waiting by Yama for three days and then has this chat with him for who knows how long in human time. Had he died physically, the chances are that he would have been cremated days before his return. Was he resurrected from the ashes? The Katha Upanishad does not say. Such questions are meaningless, not because they fail to satisfy some literalist criterion of verifiability but because the entire Upanishad speaks to us from a mythic ‘as if’ dimension, not from a literalist ‘this is so’ one.

It’s interesting that Nachiketa’s ‘mission’ is so unique that Death is taken aback by finding a guest, who has waited for him for three whole days. The 20th century German philosopher Heidegger is one among many philosophers, who have underlined the ‘inauthentic’ human condition that flees death and creates obsessive routines of ‘everydayness’ to avoid the dread (and the authenticity) of encountering one’s own death. Whereas, Nachiketa boldly seeks out Death, only to find Him missing and has to wait for him!

One can imagine Death’s loss of composure at encountering this strange young man. Quickly regaining control of himself, Yama, in a rare gesture of divine generosity, offers him three boons by way of compensation. Despite his questioning temperament, Nachiketa proves to be an affectionate son. So, his first request is restoration of harmony with his father. Yama assents to this easily enough, arguing that Vajrashravasa would be overjoyed at seeing his beloved son released from Death’s jaws. The second boon relates to knowledge of the Fire Sacrifice which guarantees one longevity, peace and great happiness in Heaven. Many have argued that the true Fire Sacrifice is internal, sacrificing one’s many chattering ego desires to the Agni within. This boon is easily granted. The third boon is the pivot on which this whole Upanishad turns. Yama (comparable here to an amiable Arabian Nights genie) asks his unexpected guest to choose wisely, as this is the last of the wishes. Nachiketa boldly asks his host to teach him the truth of what lies beyond death. Yama is secretly pleased with the courage and wisdom of his young interlocutor. He decides to fire test him to see if he’s really worthy to receive this priceless gift. Unlike Bergman’s Death in the Seventh Seal, Yama is willing to divulge the secret provided the questioner deserves the answer. Yama tells Nachiketa that this is a question that has baffled the wise through the centuries. He tempts the young man with longevity, health, wealth and all the ‘stuff’ that mortals seek feverishly. It is a measure of Nachiketa’s tough nay-saying integrity that he doesn’t want the apsaras, the cows and horses or the sensuous feast spread out for him by Death.

His argument is simple: these pleasures are short-lived. Even a long life ends ultimately in the arms of death. Death is highly impressed by his new-found pupil and initiates him into the mysteries of immortality.

He points out that the vast majority of humans, lured by the transient take the glittering path of Preya, chasing the delights of the senses and therefore condemned to an endless cycle of death and rebirth. This regressive cyclicality from one death to the next is never condemned as evil. It’s seen as immature and on par with any blinding addiction that prevents us from seeing life in its wholeness.

The preferred path, the ‘razor’s edge path’, is the Shreya route which, by detaching us from the cycle of attachment and its consequences, leads us to the hidden Self (Atman) within and thus to freedom from bondage. For, this Self is eternal, unchanging. It “slays, not, nor is ever slain,” in the words of the Katha Upanishad, words that Ralph Waldo Emerson famously echoes in his poem ‘Brahma’. Choosing this Self that lies behind all the ephemeral pleasures of the everyday life-world is a path notoriously difficult to traverse and “sharp like a razor’s edge.” Any moment, you can be pulled back by physical, emotional or intellectual addiction to the familiar death-ridden world where Yama resides.

Yama’s fork is clear: an either/or between joyful liberation from death and rebirth, or an endless succession of lives wallowing in the trough of pleasure but paying the grim price of dying over and over again.

Yama’s pedagogy offers us the most dramatic example of a Vedantic paradigm, wherein attachment to things of the world is framed not as sinful, but rather as an ignorance that keeps one chained to the recurrent wheel of death and rebirth.

Yet, here’s the rub: Yama’s fork smacks of privileging Shreya and marginalizing Preya. Despite the brave non-dualist talk of Advaita approaches, the fork points mutely to a dichotomous value system, an either/or that paints one signifier in a glorious etherial light and the other in shades of darkness and disapproval.

First published in Indian Express, April 30, 2018