The floods in Pakistan now show signs of abating but the havoc caused by them will continue to mount. It is too early to measure even the immediate losses of lives or property, both private and public, although over 2000 persons are estimated to have died and 21 million become refugees in their own country. Secondary damages to agricultural land and animal husbandry will take years to recoup. At one point about one-fifth of Pakistan’s total land area had gone under water. Floodwaters have destroyed crops : an estimated 700,000 acres of cotton, 200,000 acres each of rice and sugar cane and 300,000 acres of wheat. This will impact the agricultural economy which contributed 20.4% of Pakistan’s GDP last year. The cascading effect into industry and trade is bound to add to economic woes.

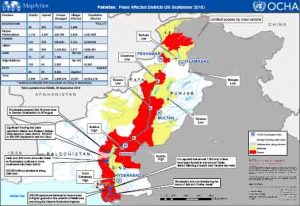

Pak Flood affected districts as on 6th September 2010 – (Source OCHA)

Scientists have described this catastrophe as a once-in-a-century flood. Out of a Population of 168 million nearly 21 milion people have been affected by floods out of a total area of Pakistan of 796 095 square kilometers, the Flood-affected area is 160 000 square kilometers. In a country where already a large percentage of the population is living as refugees, an additional 1.85 million homes have been destroyed or damaged due to floods. Look at the fact sheet of the present disaster:

Pakistan Flood Losses (as on 6 September 2010)

Source: NDMA, PDMA |

| Province |

Deaths |

Injured |

Houses Damaged |

Population Affected |

| Balochistan |

48 |

102 |

75,261 |

*672,171 |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

1,154 |

1,193 |

200,799 |

4,365,909 |

| Punjab |

110 |

350 |

500,000 |

8,200,000 |

| Sindh |

186 |

909 |

1,058,862 |

6,988,491 |

| AJK |

71 |

87 |

7,108 |

245,000 |

| Gilgit Baltistan |

183 |

60 |

2,830 |

81,605 |

| Total |

1,752 |

2,701 |

1,844,860 |

20,553,176 |

| * Additional 600,000 IDPs from Sindh are living in Balochistan |

The degree of severity to which people have been affected by the floods varies depending on their particular losses and damages. UN assessments have been launched in at least three provinces to identify severely affected families who require life-saving humanitarian assistance. The UN experts have identified 2.7 million people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 5.3 million in Punjab and 4.4 million in Sindh that are in need of immediate humanitarian assistance.

Approximately 4 out of 5 people in the flood-affected areas depend on agriculture for their livelihood. Across the country, millions of people have lost their entire means to sustain themselves in the immediate and longer term, owing to the destruction/damage of standing crops and means of agricultural production. One of the greatest challenges on the ground is helping farmers to recover their land in time for wheat planting beginning in September/October and to prevent further livestock losses. According to the FAO figures released on 3rd September 2010, the scale of losses to the agriculture sector caused by the Pakistan floods is unprecedented and further unfolding:

- The Agriculture Cluster rapid damage assessments, completed in half of all flood-affected districts, found that 1.3 million hectares of standing crops have been damaged

- Countrywide damage to millions of hectares of cultivatable land, including standing crops (e.g. rice,maize, cotton, sugar cane, orchards and vegetables) appears likely

- Loss of 0.5-0.6 million tonnes of wheat stock needed for the wheat planting season

- Death of 1.2 million large and small animals, and 6 million poultry (Department of Livestock)

While the full extent of the damage still cannot be quantified and assessments are ongoing, the direct and future losses are likely to affect millions of people at household level, as well as impact national productive capacity for staple crops, such as wheat and rice. The FAO feels that response to needs in the agriculture sector cannot be underestimated nor delayed.

The political spillover is equally if not more worrisome. Relief efforts have highlighted the inefficiencies and corruption endemic in the Pakistani administrative set-up, magnified as it is becoming in the eyes of the already disenchanted masses, especially the internally displaced. The fear is that fundamentalist organizations will extend their grip over affected populations by filling in wide gaps in disaster relief left by Pakistan Government and international relief agencies. All this adds fuel to the already political fire in a volatile and unpredictable Pakistan.

Even if Pakistan wades through the floods, what is there to prevent another water disaster in the future? To answer this question, one must examine these floods in a broader framework. Pakistani meteorological data points to unusually heavy rains in July – August in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab provinces as the main cause of the floods. Satellite pictures corroborate this.

Satellite Map shows the swelling Indus River at Sukkur Barrge Source NASA

Satellite Map shows the swelling Indus River at Sukkur Barrge Source NASA

According to a WAPDA (Water and Power Development Authority) ] press release on Water Situation on 03 – 09 – 2010 the 24 hour Inflows / Outflows (in Cusecs) of the major Dams on the rivers in Pakistan were as follows:

Indus at Tarbela 203300 / 203300 Cusecs

Kabul at Nowshera 42000 / 42000 Cusecs

Indus at Chashma 249100 / 244100 Cusecs

Jhelum at Mangla 42800 / 42800 Cusecs

Chenab at Marala 87000 / 67400 Cusecs.

The above figures indicate that the Pakistani dams/barrages are virtually unable to retain any water, as can be seen above, almost all of the inflows are equal to the outflows. This is normally the case in monsoons for some dams but the figures are shocking because not a single dam except for Marala on the Chenab has been able to absorb some 20,000 cusecs of water.

Balochistan Times (August 21, 2009) reported that since the Chashma Barrage had been filled with water along with Tarbela Dam and Mangla Dam as a result of filling of these water reservoirs, IRSA had directed the provinces to use the released water as much as they needed without any restrictions. According to IRSA (Indus River System Authority) officials, besides Mangla and Tarbela Dams the approximate inflow of water in the other rivers was 319500 cusecs and 4000 cusecs from river Kabul, all of which was being released as Tarbela and Mangla had filled completely. The CJ canal had been closed so that the Chashma Barrage could be destilled. The plus side for power starved Pakistan was that with the filling of dams with water, the power production had been increased, from which about 4000MW power was being generated from hydel power, which reduced load shedding in the country..

The flood affected areas were mostly along the main Indus River and its western tributaries – Swat and Kabul; and less so from the eastern tributaries – Jhelum, Chenab and Sutlej. This should not however obscure the overall picture. More than 80% of the total water flows in the Indus river- system is accounted for by snowmelt and rainfall in the mountainous regions which are largely beyond its political control and belong to Afghanistan, India and China. According to one estimate, the Kabul river accounts for 20 to 30 MAF of total annual flows, the main Indus 100 MAF and the Jhelum and Chenab 60, while the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej add another 40 MAF or so. Floods are a cumulative effect of all these flows.

Initially, storage dams like Mangla and Tarbela were built to modulate irrigation and control floods. But some 7 MAF of their storage capacity has already been silted up. And Pakistan has been singularly unsuccessful in building additional storage capacity to compensate, let alone provide for enhanced irrigation and flood control needs. A major project – the Kalabagh dam – has failed to get off the drawing boards for two decades because of internal bickering between its provinces. The international segmentation of the Indus basin rivers complicates the problem still further, particularly in relation to the two principal upper riparians – India andAfghanistan – with which Pakistan has troubled relationships.

The 3,200 km long Indus, one of the mighty rivers of the Indian subcontinent, flows down from the Himalayas of Tibet, towards north-west through India before turning sharply southwards through Pakistan, draining into the Arabian Sea. Some of its water comes from melting Himalayan glaciers, but the vast majority is contributed by the monsoon. The monsoon floods are triggered almost annually. Historical records indicate that during a warm period ending about 6,000 years ago, the Indus was a monster river, more powerful and more prone to flooding than today. Then, 4,000 years ago, as the climate cooled, a large part of it simply dried up. Deserts appeared whether mighty torrents once flowed. The matter of public debate is whether, with global warming, will the river again turn monstrous. A matter which further compounds the problem is the fact that siltation reduces the rivers capacity to hold water. Even with the total quantum of precipitation being the same, the intensity of rainfall gets aggravated by global warming resulting in unmanageable discharges. Pakistan, which spends more of its scarce financial resources in building defences against India, has been unable to enhance its Hydraulic infrastructure comprising of dams and barrages. In fact, due to siltation its overall storage capacity has further reduced.

Pakistan is, thus at a fork in the road. It can either continue confrontationist policies which underlie present arrangements (or lack thereof) and face similar or perhaps bigger flood disasters in future, if anticipated climate change effects do materialise. Or it can chose to cooperate with countries in the Indus basin with a view to building an integrated system of storage dams, flood control installations and power generation stations which will help to modulate flows and avert floods, thereby benefitting Pakistan’s agriculture particularly its struggling farmers. The attendant hydropower potential is also huge and can be tapped for the energy-hungry Pakistani economy, as well as cross-border sales to India. The big question is whether the Pakistan’s rulers can change their confrontationist mindset to make this possible. If there was no deficit of trust India could have stored water even in the eastern rivers of the Indus basin to be used as a kind of buffer during floods. But, for that an integrated basin management is required, because the mighty rivers, follow their own course, they do not recognize man made political boundaries.

A Condensed version of this article was first published in Hindu Business Lineon 19th October 2010. Business Line version is available on the net at the following URL:

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/2010/10/19/stories/2010101950330900.htm

Acronyms

NDMA National Disaster Management Authority

WAPDA Water and Power Development Authority

IRSA Indus River System Authority

OCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation

IDP Internally Displaced Person

MAF Million Acre Feet

Cusec Cubic Feet per Second