Creating recovery resources in mental health – 1

This is a first of what may be a set of posts around the same theme- recovery in mental health or recovery from mental health issues, regaining one’s sense of wellbeing after an emotional/psychological setback.

The past year has gone in a lot of work in this area (also among the reasons I could not write on this blog). So now is the time to talk about the work which has been done away from the public eye.

Let me begin with the book, which comes out later this year, I put to bed a few months ago. Currently the last phase of that is underway- on the production front.

As an aside, a somewhat disconcerting thought which has always been there at the back of my head is that when we say the word ‘recovery’ in the context of mental health it conjures a particular kind of image. Recovery is often mistaken to be the recognition of someone’s suffering as a diagnostic reality. (Oh, but this was not the disconcerting thought I had in mind- it was about my book and how academic it is!)

“Oh, now I know why I was feeling so bad. I have anxiety after all“.

“I got a diagnosis of PTSD and chronic depression. I was also wondering what is going wrong.”

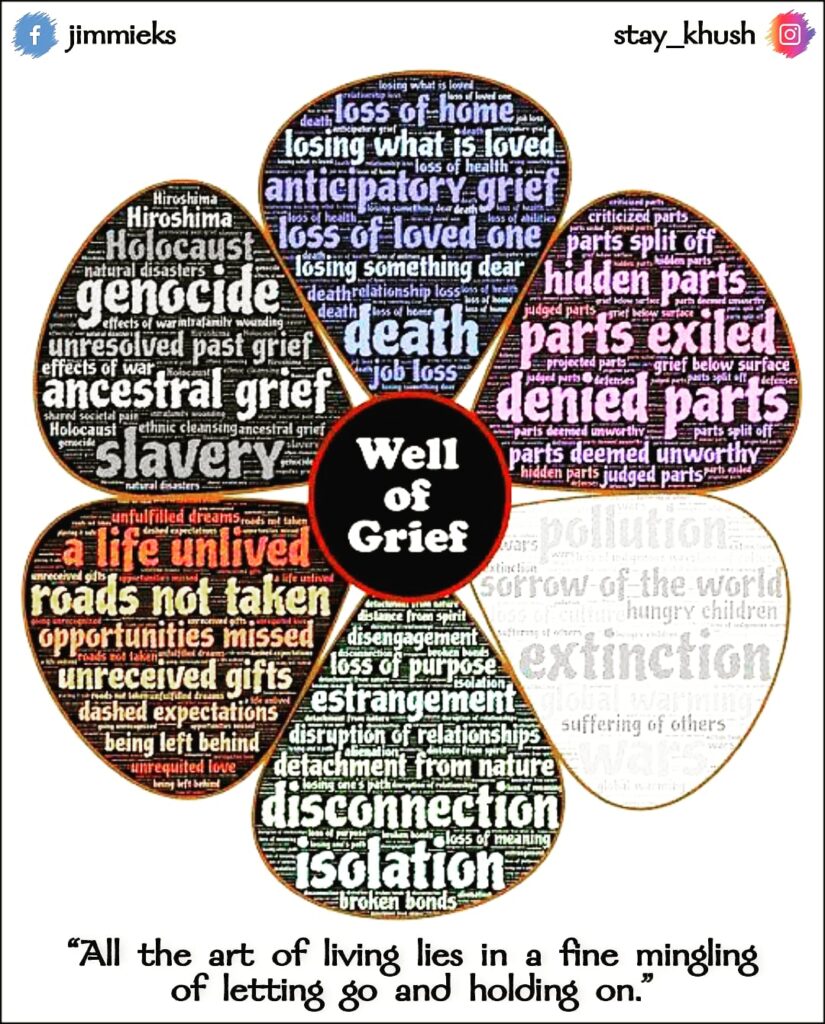

This description of suffering and its reframing into a diagnostic “truth” is what happens all the time in the field of mental health, something that troubles me immensely. But I will not go into that trouble right now. I better share with you what is the problem for me to solve here- the problem of talking about recovery.

I recovered from bipolar disorder. It may sound like something un-relatable, for one is not supposed to. In other words I am an outlier by all standards. This sudden disclosure is not part of my identity politics and I do not use mental health as a means for attention-seeking for I am troubled by it. For me my positioning is an ethical stance which comes with an agenda, largely research driven.

My agenda

My agenda post my own recovery was twosome. First it became to map my own recovery- for how did I recover?

I had no clear cut ways to share with another. I am talking about the year 2011. That was the time I started on recovery research, and a number of articles followed in diverse journals across the globe- Psychological Studies, Canadian Journal of Music Therapy, World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review and others (you are welcome to check them from my linkedin profile, ResearchGate or Academia networks. Oh yes, there is one article which is just a click away in which you can both read my (less academic) writing and hear my (self composed) songs (ghazals to be more precise). A longer piece of writing about the ghazal and its role in my healing is there in the World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review (2015).

My second agenda is/was to see if one person can recover, why are others not able to. Or rather, what is it that does not allow more people to recover- which became my PhD research (2016-2020)

Three decades in the field and five decades of life behind me, I know there was none other than this which was my goal, at least for now- recovery research. So while the research was done as a PhD and barriers to recovery found the next and more befuddling (may I say unenviable) option is how to tell others they can recover as well?

This is what I am doing nowadays- creating those other resources to disseminate the findings from my work, advocacy about recovery from mental health issues and suchlike things.

I am not going to say further in this post except having introduced the context- of who I am, where I come from and why I talk about recovery so much. And yes the resources I am busy creating- resources for recovery, advocacy and helping others recover just as well as me.

The first put to bed was the book of course. I will talk about it closer to the time it publishes (later this year)

The second is DIALOGUES FOR RECOVERY with the support and handholding by Vidya Sagar, Chennai. Here is a sample of that work, though we are not yet adept with this sort of work. Whatever else is unfolding is still firming up and I will share about them in subsequent posts. But I invite you to read the writing I have shared, which are scores of articles about my recovery and where I stand today, or what ideas I propagate via diverse means. The video that follows is a sample. There are at least five others of its siblings you can check from the same link and you get to hear my other ideas too (not mine solely, of course for we all stand on the shoulders of giants after all) …